The Mexican Wolf Reintroduction

Project

Understanding Diverse Viewpoints

Introduction

The Issue at Hand

The Mexican wolf used once roamed

throughout the Southwestern United States and Mexico. However, due

to an eradication plan supported up by the United States Biological

Survey in the early 1900's, the Mexican wolf was completely eliminated

from the United States. Only about 25 remained within Mexico (Brown).

With the passing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973, the remaining

Mexican wolves were captured and placed in captive breeding sites throughout

the nation, with the intention of reintroducing them into the wild.

In the meantime, the US Fish and Wildlife Service conducted extensive

research in preparation for the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)

that was required for this reintroduction program under the National Environmental

Policy Act (NEPA)

. The Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) was made available

to the public in November

1996. This document includes locations and

desired numbers of wolves for each reintroduction site. It defined habitat

distributions, management protocols and alternatives, and the ecological

assessment, describing the feasibility ofdifferent reinroduction sites

to sustain wolf populations. A major portion of the FEIS is devoted to

the effects the wolf will have on its surroundings, including the communities

of ranchers and Native Americans that utilize the land adjacent to

the the proposed reintroduction areas, located in the Apache and Gila

National Forests ("Reintroduction").

In 1998, with the support of Arizona and New

Mexico Game and Fish, and the help of leading wolf biologists, USFWS

released 11 Mexican wolves into the Apache National Forest in Arizona.

Since that time, USFWS has faced many difficulties, including devising

a management plan that was both politically and economically feasible.

The largest difficulty has been in appeasing the different stakeholders

involved and affected by the project. Some groups, like the ranchers

and Native American tribal members found in the areas surrounding the

introductions sites, have openly opposed the reintroduction. Other difficulties

have come from environmentalists, who have heavily criticized the management

protocols and have pushed for a more accessible public information

forum. Meanwhile the State Governments of Arizona and New Mexico have also

filed mixed reviews. As recently as March 29, 2002, New Mexico was threatening

to pull out of the project alltogether, and to permanently close the

gates of the Gila National Forest to the Mexican wolves ("New Mexico").

Under the Mexican wolf FEIS, the objective

of the USFWS is to establish establish a wild population of 100

individuals by 2005 within a 5,000 square mile recovery area, while

keeping 240 individuals in captivity to be used in maintaining genetic

viability ("Reintroduction," 1-1). However, despite the fact that the FEIS

focuses on the wolves, it often seems as if the federal government is more

concerned with meeting the desires of all the people affected than

to meeting the goals set up for the project. In the 21st century, with

a human population of over 6 billion, pristine areas no longer exist, for

all areas of the Earth are now somehow impacted either by human action or

by human thought (Allenby). Therefore, to truly be an effective manager

of any pristine area (or wildlife, in this case), it is important to

understand the human components that are involved in the management protocols.

The viability of the Mexican wolf population depends not only on the effectivenes

of the USFWS to execute a federal law; it also depends on the open-mindedness

of the people who live around the reintroduction area. These individuals

may feel that the security and control within their land is now threatened

by the return of an animal that they, or their ancestors, had helped to

eradicate.

In order to correctly manage the wolf within this human

sphere, we must understand the relationship between humans and the wolf.

In order to understand how to most effectively manage the Mexican wolf,

it is imperative to understand the thinking and motivation of the federal

government, the environmentalists, the ranchers and the Apache tribes.

The federal government has legal jurisdiction over the issue. The environmentalists

are the most passionate about the issue. The ranchers and Apache, local

citizens of the areas juxtaposing the reintroduction sites, are most

directly affected by the wolves, for it is these two groups who will have

most interaction with the wolves.

Brief History

The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), otherwise

known as the Lobo, is the smallest, most genetically distinct

subspecies of the gray wolf. Historically, the Mexican wolf ranged throughout

the oak woodlands, mountain forests, grasslands and scrublands of America's

Southwest, in the states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and throughout

Mexico. However, with the increases in cattle numbers in the Southwest

in the late 1880's, conflicts between the lobo and cattle increased

in frequency. This quickly prompted the USBS to creation a plan that

called for the eradication of every single wolf throughout the United

States. Under the bureau's Predatory Animal and Rodent Control Service

(PARC), hunters were paid today's equivalent of $175 to either kill

or capture a wolf. Wolves were killed using traps, which came in different

shapes and sizes and were appropriately placed, anticipating a wolf's

movement. Denning was another favorite hunting techniques, whereby hunters

located active dens and killed the pups. Lastly, hunters also reduced

wolf number dramatically through their use of the the poison strychnine.

This method was actually one of the most efficient and cost effective,

for it required less maintenance than a trap did. Also, using strychnine

was much cheaper than sending out a hunter to kill three pups in a den,

for one application of this chemical could potentially kill a dozen or more

animals. In general, the eradication program was so successful that not

only were over 900 wolves killed in a single 10 year span from 1915 to 1925,

but, less than one hundred years later, every Mexican wolf within the United

States was dead. Only about 25 remained in Mexico (Brown).

However, with the passing

of the Endangered Species Act, steps were quickly taken to reestablish

the Mexican wolf population and reintroducethe wolf back into the

wild. The federal government, so implemental in the destruction of

the Mexican wolf, now became one of the main proponents for its return

to the Southwest. Using Mexican wolves acquired from Mexico, a captive

breeding program was set up amongst 24 zoos and wildlife sanctuaries

across the country. By 1996, the Final Environmental Impact Statement for

the Mexican wolf reintroduction was completed and released to the public,

signifying that the reintroduction program had officially begun ("Reintroduction,"

1-1 - 1-5).

On March 29, 1998, about 25 years since

they had been completely eradicated from the United States, and almost

brought to extinction, 11 Mexican wolves were released within the

primary recovery zone of the Apache National Forest in Arizona. Today,

having been returned to their native habitat, about 25 of them are once

again roaming free in the Southwest.

The Management Plan

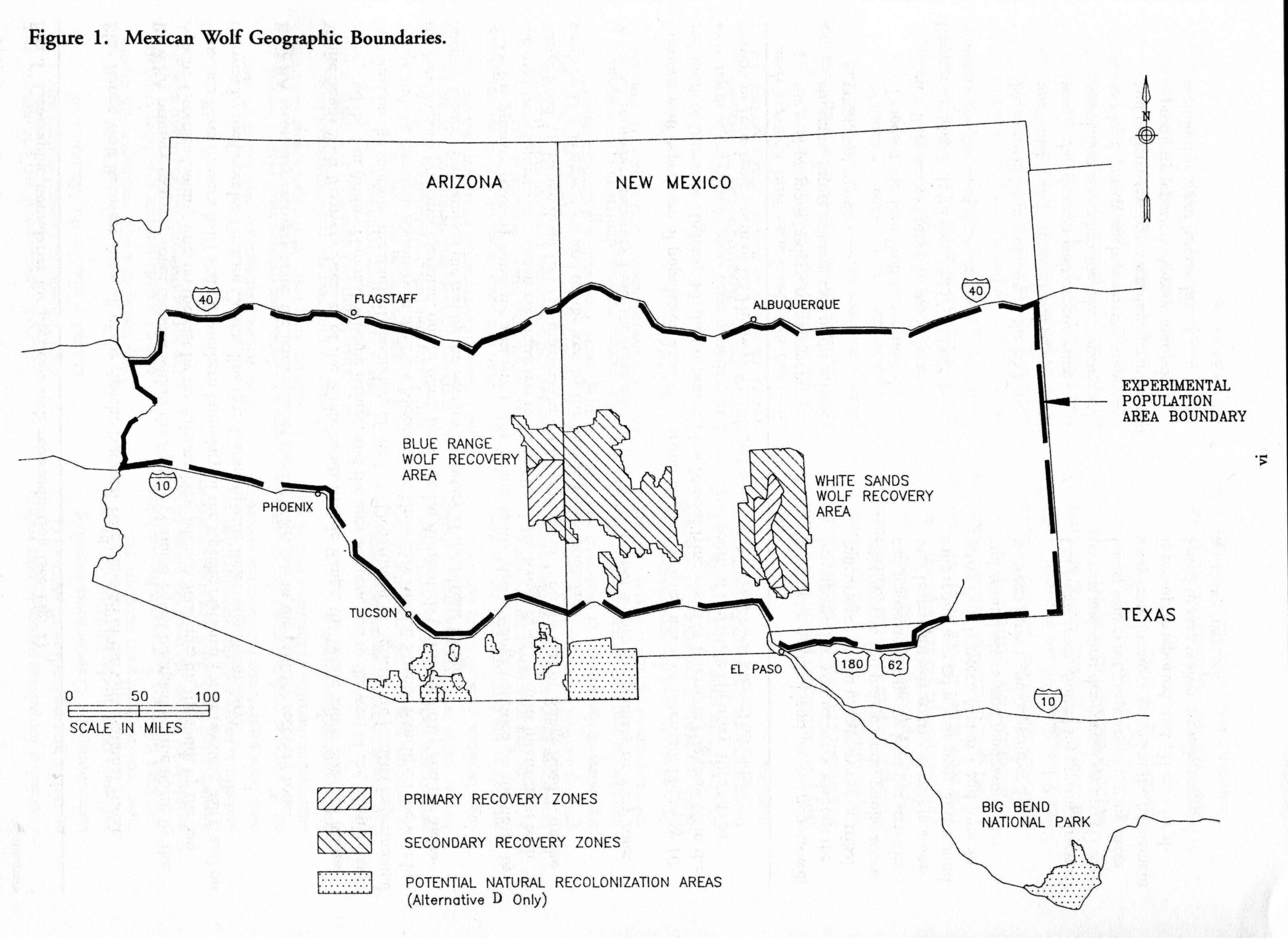

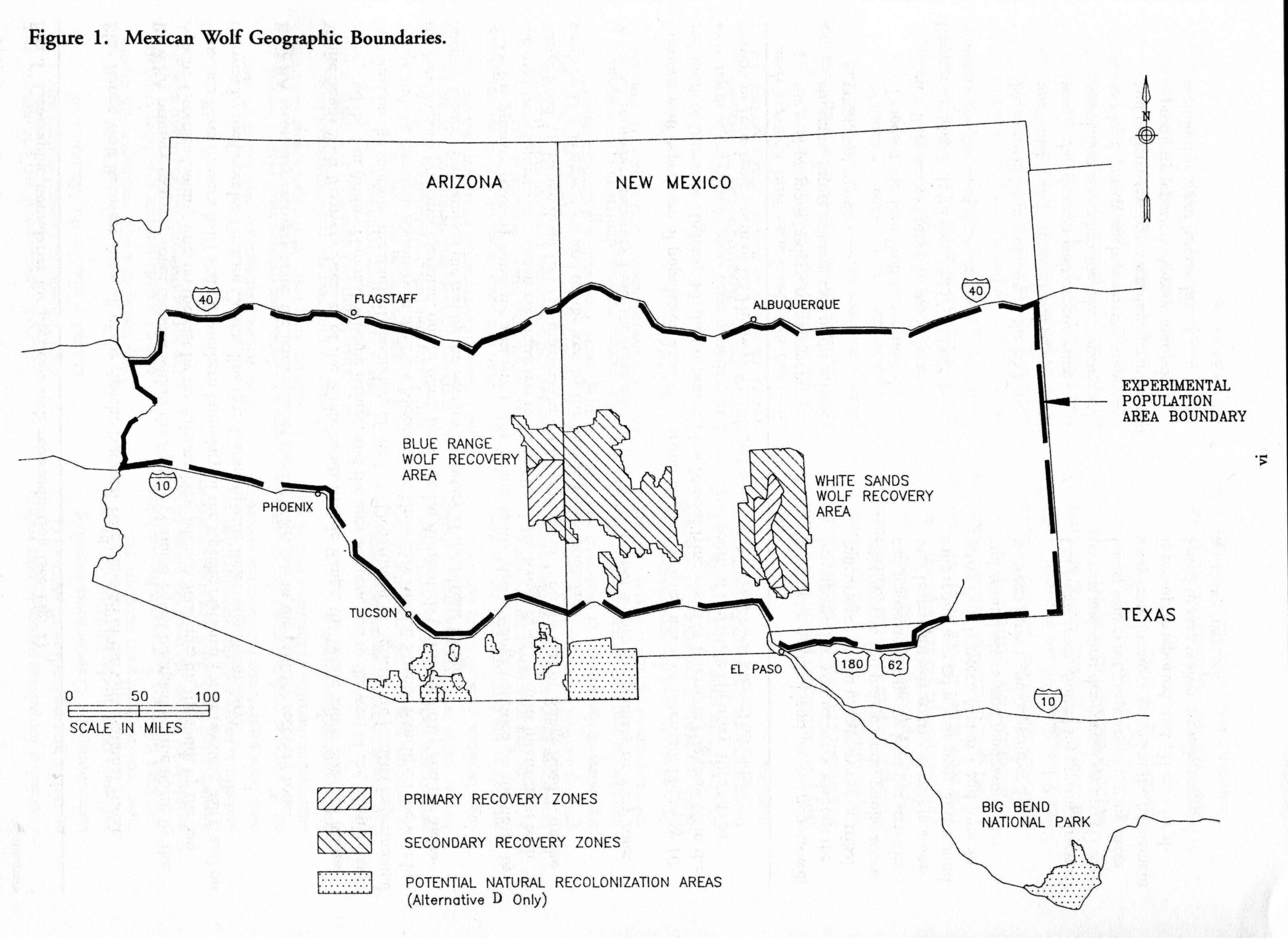

The goal of the original plan, outlined in the Final Environmental Impact

Statement, is to establish a wild population of 100 individuals by 2005 within

a 5,000 square mile recovery area, while keeping 240 individuals in captivity

to be used in maintaining genetic viability. Under Alternative A, the option

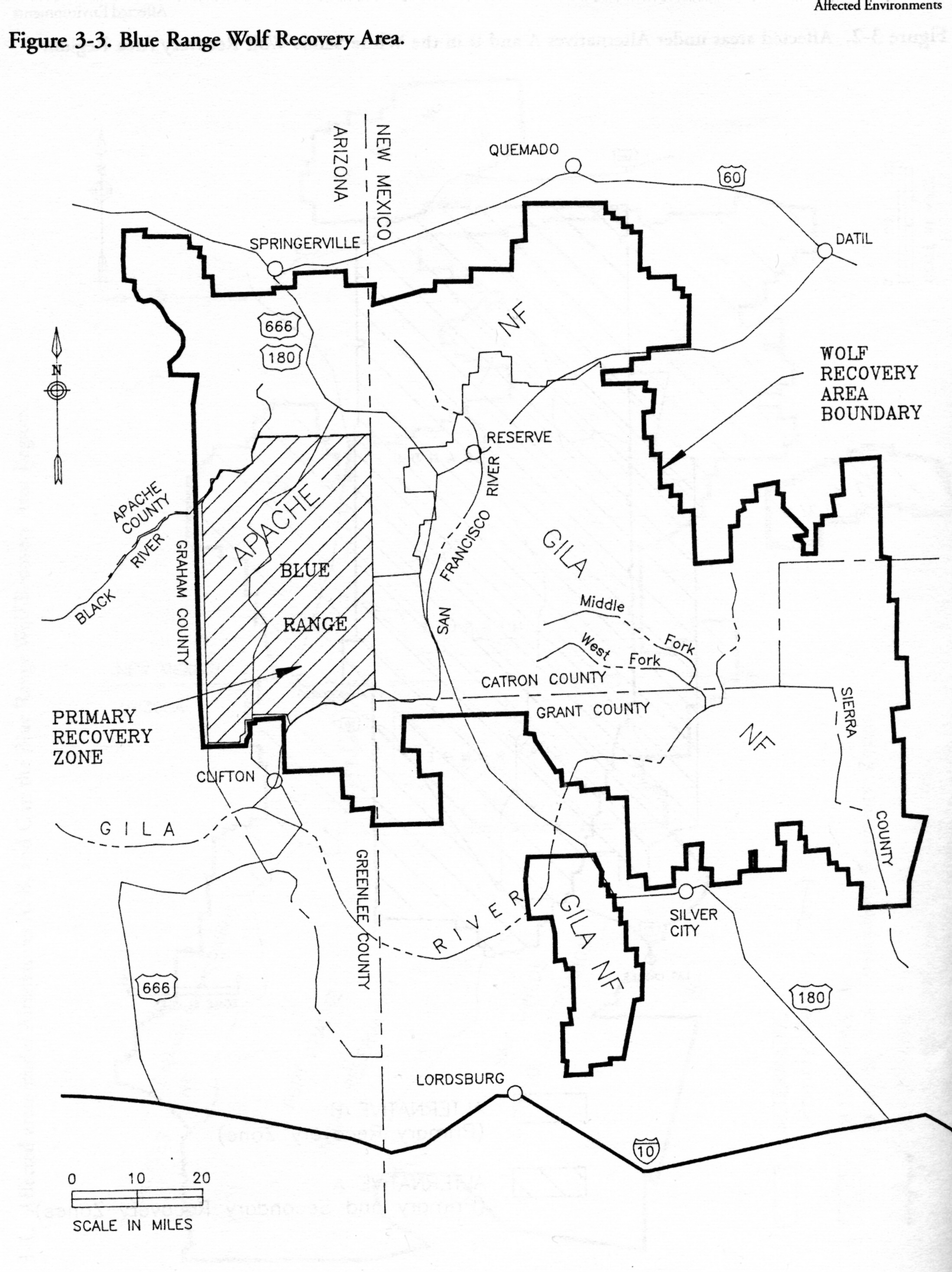

that was adopted, the FWS designated the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area

(BRWRA) as that area which includes the Apache National Forest, AZ and Gila

National Forest, NM (figure 1). The plan includes initial reintroduction of

the Mexican wolf into the primary recovery zone of the Blue Range Wolf Recovery

Area (figure 2) - the southwestern corner of BRWRA. The plan allows for up

to 15 families to be released within the area, and for the dispersal of these

wolves throughout BRWRA. The option has been left open for release of up to

5 families within the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area, located east of BRWRA.

The White Sands Recovery Area, NM includes the White Sands Missle Range, the

White Sands National Monument, the San Andres National Wildlife Refuge and

small portions of surrounding federal lands ("Reintroduction," 2-5 - 2-7).

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2

Currently, the Mexican wolf is designated

as nonessential experimental, since the population currently in the wild

is not essential to the genetic viability of the species. This designation

has allowed the USFWS to have a more active management scheme, as

opposed to the management scheme adopted in the case of the endangered

Red Wolf in North Carolina. The red wolf is given more freedom to disperse,

and currently can be found within the Alligator River National

Wildlife Refuge in northeastern North Carolina and Great Smoky Mountains

National Park in the Southern Appalachian Mountains ("Red Wolf").

In the case that Mexican wolves disperse outside their designated reintroduction

area (the BRWRA), the USFWS must intervene and relocate them back

to the BRWRA. The federal government will not intervene only in

the case legal residents have allowed the wolves on their land ("Reintroduction,"

2-5 - 2-17). Recently, the area open to the

Mexican wolf has increased. On March 28, 2002

, the White Mountain Apache Tribe ruled to allow up to six wolves

onto 1.5 million acres

of land on their reservation ("White Mountain").

In addition to the active management plan, USFWS

have also adapted an "adaptive management approach" with regards to

the Mexican wolf reintroduction project. Under the adaptive management

strategy, USFWS is able to alter the management protocol based on professional

and public recommendations, and the results of research and monotoring

of the released wolves ("Reintroduction," 2-5 - 2-17).

|

|

|

|

| Author:

Yekaterina Gluzberg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Updated: 14 May 2002 |

|

|

|

The goal of the original plan, outlined in the Final Environmental Impact

Statement, is to establish a wild population of 100 individuals by 2005 within

a 5,000 square mile recovery area, while keeping 240 individuals in captivity

to be used in maintaining genetic viability. Under Alternative A, the option

that was adopted, the FWS designated the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area

(BRWRA) as that area which includes the Apache National Forest, AZ and Gila

National Forest, NM (figure 1). The plan includes initial reintroduction of

the Mexican wolf into the primary recovery zone of the Blue Range Wolf Recovery

Area (figure 2) - the southwestern corner of BRWRA. The plan allows for up

to 15 families to be released within the area, and for the dispersal of these

wolves throughout BRWRA. The option has been left open for release of up to

5 families within the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area, located east of BRWRA.

The White Sands Recovery Area, NM includes the White Sands Missle Range, the

White Sands National Monument, the San Andres National Wildlife Refuge and

small portions of surrounding federal lands ("Reintroduction," 2-5 - 2-7).

The goal of the original plan, outlined in the Final Environmental Impact

Statement, is to establish a wild population of 100 individuals by 2005 within

a 5,000 square mile recovery area, while keeping 240 individuals in captivity

to be used in maintaining genetic viability. Under Alternative A, the option

that was adopted, the FWS designated the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area

(BRWRA) as that area which includes the Apache National Forest, AZ and Gila

National Forest, NM (figure 1). The plan includes initial reintroduction of

the Mexican wolf into the primary recovery zone of the Blue Range Wolf Recovery

Area (figure 2) - the southwestern corner of BRWRA. The plan allows for up

to 15 families to be released within the area, and for the dispersal of these

wolves throughout BRWRA. The option has been left open for release of up to

5 families within the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area, located east of BRWRA.

The White Sands Recovery Area, NM includes the White Sands Missle Range, the

White Sands National Monument, the San Andres National Wildlife Refuge and

small portions of surrounding federal lands ("Reintroduction," 2-5 - 2-7).